Becoming a keeper of resistant honeybees

Warning: Advice can change but this is the best current advice based on scientific findings and beekeeper experiences

The History of Varroa resistance

Varroa resistance outside of Asia first appeared in Africanised honeybees (AHB) in Brazil. Initially resistance was thought to be due to a less virulent type of Varroa, but this idea was later proved wrong. AHB rapidly spread northwards through the Americas, reaching the USA. Studies in Mexico and Brazil in the 1990s found high levels of mite infertility in AHB colonies, although the reason was unknown. Other proposed resistance mechanisms like ‘grooming’ became popular but suffered from flaws in the study design and overlooked the fact that the smell of Varroa is the same as the bee (chemical mimicry). In Ron Hoskins colonies it was suggested DWV-B caused resistance via ‘super infection exclusion’ but again this was later shown to be incorrect as wider surveys found DWV-B in most UK colonies. Bee breeders attempted to select for Varroa resistance, but these largely failed since the resistance mechanism was still unknown. Several breeders used the pin prick test or the freeze-kill brood to check for colonies that would then remove the dead pupae. The major flaw in this approach is that Varroa doesn’t kill the pupae so the chemical cues from dead and living infested brood are different. The breeders were selecting for bees that could detect dead brood not Varroa mites.

During this period before the link between recapping and resistance was made in 2018, resistant populations were starting to be studied. In South Africa and Cuba central decisions not to treat resulted in resistant populations appearing 5-8 years later. In the Arnot forest in New York State, Tom Seeley had monitored the return of resistant wild honeybees in the forest, likewise in France two other resistant populations were studied. Finally, a small number of beekeepers in the UK and elsewhere were managing their colonies without treatment most notably the Hudson’s of North Wales and Ron Hoskins of the Swindon Honey Bee Conservation Group. After the breakthrough study in 2018 we can now explain how the 3 traits associated with resistance are linked and how these explain resistance in almost all previous cases mentioned. The number of beekeepers that have not treated for over 6 years in the UK continues to increase. If you want to join them and be free of treating, read on.

Going treatment free - the options

1. Don't treat and let the bees sort it out

This approach can work very well on a very large scale as seen in Cuba and South Africa, but in the UK this option has a high degree of failure that increases with the fewer colonies you have. There are UK examples of this working where colonies have been abandoned due to beekeeper illness etc and then discovered to be alive several years later. It is, however, not always easy to be sure that it is the same colony in there and not a recent swarm. Ron Hoskins of the Swindon Honeybee Conservation Group is the only UK person we know that has succeeded with this approach after initial colony losses, but at the same time dozens or even hundreds of beekeepers not treating lost all their colonies.

2. Collect/buy resistant bees

The collection of feral resistant swarms is an excellent way to obtain resistant colonies and is often used. This is how the North Wales group got started and many Hawaiian beekeepers. The key is having access to a location where feral colonies appear to have persisted for many years. Be aware that not all colonies living in trees or buildings have been there for long periods of time.

The other way is to buy a colony/nuc or queens from a local person that has a well established population of resistant bees i.e. zero treatment for 10+ years. Although currently there is no one offering this service we hope things will change in the future.

3. Reduce treatments over time

For beekeepers that do not have access to resistant feral or managed colonies this is the best option for you. We now have one of our group (Steve Riley) that is doing this successfully. There is also not one way that will suit everyone.

The current basic advice is reduce your treatments by either halving what you are currently doing, or moving out to a less efficient treatment e.g. changing an Oxalic acid treatment for sugar dusting or changing annual treatments for bi-annual treatments. But in each case ensure you monitor your mite levels and treat or remove any colony with high mite levels.

Advice on how to achieve each option

1. Don't treat and let the bees sort it out

Pros;

- Easy

- Just need to wait

- Mimics what happens (or is happening) in our feral colonies

- Can happen by accident

Cons;

- Needs to be done on a large scale

- Potentially years of high colony losses to be endured

- Unlikely to work in UK

- Totally unsuitable for any commercial operations

As this is not really a viable option for UK beekeepers it is not worth discussing it too much. The only time it can work is when it's used by a beekeeper with dozens of colonies and a sub-set of these are placed into separate apiaries and are not treated. Any failing colonies need to be removed and replaced by splitting the strongest surviving colonies. This continues until annual colony mortality drops to that of treated colonies. As this method lies between options 1 and 3 it is discussed under both headings.

2. Collect or buy resistant bees

Pros;

- No waiting time

- Free if collecting wild swarm or given resistant bees or queen

Cons;

- No reliable way to tell if a free-living colony is resistant

- Currently no suppliers of established resistant bees in the UK (we expect that to change)

- Cost if buying bees or queens

Collecting resistant bees

Free-living colonies can represent a reservoir of Varroa resistant bees that can be used in apiculture.

This is a well-established, common, and arguably the easiest method to get started beekeeping with resistant bees. Stephen has seen on Hawaii a treatment-free beekeeper that went from 5 to 200 hives in just a few years by placing swarm boxes into the surrounding mountainous forest. The largest group of treatment-free beekeepers in the UK also got started when Clive and Shan Hudson collected swarms from the surrounding forest, then by splitting colonies passed them on to other members of the local beekeeping association. Now around 100 beekeepers spread all over the Llyn peninsula, North Wales, are managing over 500 colonies without Varroa treatment. Another example is Joe Ibbertson who has studied and collected swarms from long standing free-living colonies.

In all of the above examples, the beekeepers had access to local well established free-living colonies. In spring 2010 a study across England of free-living colonies was conducted. They suggested the main source of free-living colonies was from managed colonies and therein lies the problem. In areas where free-living colonies out number managed colonies they will become resistant via natural selection as has happened in many places. Likewise in areas where predominantly resistant bees are managed so the free-living colonies will also be resistant. So the success of this method will vary depending on the location. But an option is to collect a free-living swarm and look for the signs of resistance. Mite levels should be monitored and if they become high then the mites should be managed.

Buying resistant bees

Buy locally should always be your go to option

Currently in the UK you can buy unproven 'resistant' bees from breeders. From the information available most are using the removal of dead brood assay or advertising they are VSH selected bees. As mentioned earlier, the freeze-kill and pin prick tests are not selecting for Varroa resistance. Check the source and find out if they provide credible evidence that their colonies can survive for at least 6 years without treatment before you buy. Since we suggest that is the benchmark required to claim your bees are resistant. We estimate from a recent study that around 3,000 beekeepers spread all over England and Wales have been managing resistant colonies for 6 years or more. Currently very few are selling queens or splits to local beekeepers but we hope in the near future that will change, so watch this space.

If you do buy resistant bees and move them to an area where the surrounding population is not resistant then you will need to monitor future generations to ensure that they are managing their mites. Varroa resistance seems to be very heritable but most beekeepers do not have control over the local drone population who will contribute their genes.

3. Reduce treatments over time

Pros;

- Use your own colonies

- Make it as simple or complex as you want

- Reduce costs and time of treating

Cons;

- Takes several years

- Increased mite monitoring

Research has demonstrated that any population, irrespective of race, environment, hive type etc can become resistant. All your bees need is TIME to learn to associate the unique smell of an infested cell with the presence of Varroa. Like all learnt behaviours workers need time to make the association. We know from a French team that all bees can detect the unique compounds produced by infested cells, but only resistant ones open up to investigate the infested cells. If you choose this approach, your role as beekeeper is to reduce your treatment to allow sufficient mites so the bees can learn but not enough to have an impact on the health of your colony. How you achieve this will depend on many factors, Colony numbers, timing, and type of treatment etc.

Some general advice is first reducing your treatments. If you treat with Oxalic or Formic acid then switch to a less efficient bio-technical method e.g., sugar-dusting, queen trapping, drone brood removal, etc. Alternatively, halve the number of chemical treatments., Firstly stop any winter treatment as this has no impact on overwintering survival rates as this has been determined by the infestation rate of pupae destined to become overwintering bees back in the previous autumn. If you treat once a year, then switch to treating every other year. Monitor your mite levels particularity prior to overwintering brood production in late August and treat only if necessary. To summarise this approach: double your Varroa monitoring, half your Varroa treatments and manage colonies that have high mite counts.

4. Ongoing Management

Whichever method you use to achieve resistant bees, you should then make increase or raise queens from your best. The ‘best’ can mean different things to different beekeepers. For Varroa resistance, colonies with low mite numbers must be a priority. Varroa resistance can exist alongside lots of other traits and so Varroa resistant colonies are not a particular type, they are as varied as any non-resistant population. Ideally you will work with your local bees and encourage others to value resistance traits to build a population as Lleyn & Eifionydd BKA have done very successfully.

If you keep bees in an area that has a high density of colonies and the beekeepers do not share your goals of Varroa resistance and working with local bees then you need to check that your new colonies are continuing to manage their mites. Check for the resistance behaviours and requeen, rehome or manage those that are not resistant.

Ask advice of someone in your association that already keeps resistant bees, almost every association in England and Wales has someone that already has or is trying to become a keeper of resistant bees.

Use all the resources on this website and elsewhere.

Beekeeper Examples

What follows is a series of examples written by a beekeeper how they became to manage resistant bees.

UK

Michelle Ernoult (Treatment free for 14 years)

I started beekeeping in 2006. At the time there was a beekeeper with a hive at the allotments where I have a plot. He was moving and wanted someone to take over the hive. I liked honey so thought “why not?”. I knew absolutely nothing about honey bees. I joined the local beekeeping association, got some hands-on experience and did the beginners winter course. At the time it was generally believed all the feral or wild colonies of honey bees had been wiped out by varroa and without beekeepers treating bees they would die out.

For the first few years I treated with Apiguard – trays of a thymol-based gel. The bees absolutely hated it. As soon as the treatments went on the hives you could hear the contented hum of the hive change to an angry buzz. I learnt to stay away from the hives whilst the treatments were on because the bees would be tetchy and likely to sting. I attended a couple of integrated pest management days and a talk on oxalic acid really concerned me. If we needed to protect ourselves so carefully before using oxalic acid, why were we using it on the hives? Treating for varroa seemed a bit contradictory. Bees were facing a lot of problems, stress we were told was making those problems worse, and yet we were stressing the bees with the treatments we were using. I had also heard a view that maybe beekeepers are breeding weaker bees by propping up weak colonies which would have died out under natural selection.

I decided to stop treating for varroa. I took the rather harsh view if a colony did not survive maybe it was for the best. I didn’t mention this to other beekeepers as it was not a popular view at the time. I avoided discussing varroa levels in colonies, treatments etc. I had no idea of the varroa level in my colonies. As I wasn’t going to be treating my colonies, I didn’t see there was much point in knowing the varroa levels as it was just something else to worry about. Surprisingly my colonies didn’t all die out, in fact my colony losses seemed to be lower than the average.

Four years later I doubted my decision. I had mentioned I didn’t use treatments and been asked why I wouldn’t help my colonies. If there were treatments out there for varroa why was I not using them and did I want to lose my bees. I decided I was a terrible beekeeper and really should treat my colonies like everyone else around me appeared to be doing. I treated one colony before I was called away because of a family bereavement. I didn’t get to treat the other colonies. That year I lost one colony – the colony I had treated. All the others were thriving. I haven’t treated a colony since.

The most colonies I have kept is 8, but usually around 4. I have lost colonies during the winter, but not many. For a lot of years I have been interested in long hives and top bar beekeeping. Last year I decided to shake things up, switch to long hives (although mine have frames), stop using foundation and maybe try breeding a few queens (something I haven’t done before).

After avoiding discussions on varroa and any talks about varroa, I went to Steve Riley’s talk at The National Honey Show – The Honey Bee Solution to Varroa. It was amazing to discover there was a reason other than just luck my bees had survived my lack of treatments. I can now start looking for signs of varroa resistance in my bees and, when I do breed queens, breed from the better colonies.

Sweden

Erik Osterlund

Erik is the main driving force when it comes to helping establish Varroa-resistant honeybees in Sweden. The latest information on the situation in Sweden is given on the latest meeting of treatment-free beekeepers held on 9 Nov-2024. To view the update click on the link click on this link

UK

Joe Ibberston

Joe has never treated his bees for the past 14 years, and studies the free living colonies on the Broughton Estate. Joe has written an in depth article, supported by data, which was published in Bee Craft in Oct 2024. For the full article click the following link click on this link

WALES

Clive and Shân Hudson (Lleyn & Eifionydd BKA).

We live in Snowdonia, north-west Wales, and have been enthusiastic beekeepers since 1985. We found varroa in our hives in 1998 and treated with chemicals until we made two observations. Firstly, we noticed that varroa numbers in our hives were reducing year-on-year. Secondly, and of particular significance, we found long-lived colonies in buildings and trees; and these bees were surviving without any treatment. At first we used Bayvarol strips for nine seasons until the mites became resistant to the chemical. We then changed to using 2 teaspoons of thymol crystals on cloth placed across the brood frames. In 2009 we treated some hives with thymol and did not treat others. We could see no difference between the colonies, and have not used any treatment since. We still see varroa in our hives, although increasingly rarely; they are no problem, and we enjoy our beekeeping exactly as we did before varroa arrived. We are members of Lleyn & Eifionydd BKA, where most members keep bees without using any miticides. More information about our treatment–free experience on our website https://beemonitor.org/

James McMullon (Lleyn & Eifionydd BKA)

I have been interested in keeping bees and as a first step I joined the local Lleyn & Eifionydd Beekeepers association and attended my first meeting in October 2018, to find out more. In 2019 I was put together with a mentor, George Burgess, with 50 or so years of experience, and met with him at the association apiary, for a few Sundays of tuition through the season plus I helped him in his 3 apiaries at every opportunity. I saw the occasional bee with deformed wing, occasional chalk brood in weaker colonies. Fortunately, in our area there is a long history (more than 10 years) of not treating for varroa, and colonies are able to control it. In the summer of 2019, I got my first colony as a nuc from the association apiary and my second as a complete hive from George. The two colonies produced about 15 lbs of honey in that first year and survived the winter with syrup in the autumn and candy in Jan/Feb 2020.

In the 2020 season I split one of the colonies to control swarming (the other superseded late in the year) and bought 2 more colonies from a local beekeeper who was giving up. All 5 survived the winter. I have never treated for varroa, and would not know how, although I think that if I ever saw one of my colonies suffering badly from deformed wing virus, I would not be looking to help it with chemicals anyway, best to let the bees deal with it themselves or die out. Last year I peaked at 14 hives in 2 apiaries (I took over 5 existing colonies at the second apiary) and produced about 400 lbs of honey, I combined colonies to reduce to 10 over the winter as of the middle of Feb 2023 all are still going.

John E Owen (Glamorgan to Haverfordwest)

I have been keeping bees for 50 years and run over 80 colonies in 6 apiaries from the Vale of Glamorgan to Haverfordwest in Wales. I have been treatment free for 6 years.

I was inspired to go treatment free after an apiary meeting hosted by Clive and Shan Hudson from Llyn & Eifionydd Beekeepers in north west Wales. Also, from hearing that South African beekeepers never took up treating and varroa isn’t a prominent issue there now. Monitoring for varroa and treating was taking up so much of my time and getting nowhere - bit like a dog chasing its tail. We don’t treat for Acarine or Nosema, so I decided to stop treating. In the first 3 years, winter losses varied up to, but not over 20%. Now they have normalised at around 10% and I have bigger issues than varroa from chalk brood in one apiary, possibly due to bees brought into the area.

I make increases from colonies that perform well, cope with varroa, have a low propensity to swarm and are gentle to handle. Importantly for me, these are native or near native bees which are strong flyers, resilient and suited to the Welsh conditions. Colonies that don’t fit these criteria are re-queened from stock that does. National hives are mostly used with solid floors, which helps with brood build-up in cooler conditions.

Honey and also treatment free nucs are sold locally. Contact John E Owen: eifionow@gmail.com

ENGLAND

Rhona Toft (Foragers Bee & Honey Co, Worcestershire)

My husband Richard and I live in the South of Worcestershire and started beekeeping in 2000 as a hobby. Varroa was already well established in the UK and so we followed the guidance and used Varroacides in our colonies. I was teaching organic horticulture at the time and so using Varroacides did not sit comfortably with me. I also began to notice free-living colonies in buildings and was regularly called to collect swarms from them. How did those bees survive without varroacides? Some of our bees had the same genetics! I also had the pleasure of listening to a talk by Ron Hoskins and his experiences of Varroa resistant bees. So in 2007 we stopped using Varroacides on our bees and they all survived that 1st Winter. That was (naively) enough to convince me to work towards developing a resistant population. We increased monitoring and used biotechnical controls such as sugar dusting. We only had a few colonies but there were big differences between the numbers of mites falling onto the monitoring boards. We did see a lot of immature mites on the boards and didn’t know the significance of that. We also observed bald brood in a lot of colonies. Colonies that had high mite numbers were shook swarmed and had their drone brood trapped and removed. Those with low mite numbers were used to raise Queens and drones. Winter losses were usually the same as those reported by other local beekeepers or sometimes lower. We have had an occasional bad year for losses but most beekeepers do. We have gradually increased the number of colonies and apiaries and now rarely monitor mites or take action regarding Varroa. We regularly see bald brood and cannibalised pupae and have bees that recap a high percentage of brood cells. We occasionally spot a colony that is struggling with mites and will give it a shook swarm or remove the sealed brood from it. As we are in an area with a high density of colonies, mostly treated and with some beekeepers who bring bees in to the area, we are always on the lookout for that occasional colony that might have an issue with Varroa. In 2022, we only intervened with one of our colonies. The hobby has grown over the years and we now manage up to 80 colonies as a small business. www.foragershoney.co.uk

Steve Riley (Westerham Beekeepers)

"A group of seven like-minded Westerham Beekeepers started a project in 2017 to find varroa resistant bees. Collectively, we had always been uncomfortable applying chemical miticides to our colonies and were increasingly interested in why honeybees were surviving without beekeeper intervention." To read their fully illustrated story click on this link.

Grace Evans (Lincolnshire)

I collected a swarm from a chimney where wild bees, (according to the owner) had been living there for approximately 20 years. This was in September, I didn't treat them, and they came through the winter, no problem. I then carried on breeding from this source, and I now have over 100 hives. I haven't treated for 10 years, and I completely forget that others must treat their bees, I just let mine get on with it. I have no need to mess about with treatments, I can extract honey whenever I like and don't have to worry about chemicals in the hive. I am also about to make my own foundation, so I don't have wax from beekeepers who treat. I notice uncapping and the odd dead pupae in the entrance. I very rarely see varroa. I am also a member of the bee farmers association.

Fenapiaries.com

Joe Ibbertson – Treatment Free story

I have never been a treating beekeeper and for a few reasons. Having lived next to large expanses of natural habitat in Germany, I had watched free living colonies as a young man. The idea that honeybees must be able to adapt to new pests and pathogens was already in my mind….otherwise they wouldn’t exist. Even in 2010 when I started learning, the rhetoric repeated within BKA’s didn’t match certain beekeepers’ experiences and the developing scientific literature. However naïve this venture may have seemed for a complete novice, I was prepared to rear queens, make splits and treat if necessary. It wasn’t necessary.

My approach was simplistic – attempt to mimic nature. Ironically, I had quickly become aware of numerous free-living colonies in my area, from which I collected multiple swarms. After some years faffing about with different ‘hive systems’ I’d gone full circle and settled on standard brood box with a Queen excluder. However, I’d incorporated multiple entrances, a no feeding/combining approach, low density apiaries and perpetual roof insulation (like a Warrè hive). I didn’t experience anything exceptional. I didn’t see anything cataclysmic. Losses were experienced during winter. The largest of which were in the fourth and fifth winter after building up colony numbers with swarms. Things quickly settled and over the last six years my losses have averaged 12.6% (compared to my regions 18.4% for the same period). Being a mentor to new beekeepers presents the most obscure problem of asking them to approach Varroa in a way that differs from the common narrative.

The most fascinating aspect for me has been watching behaviours like uncapping, the removal of pupa, low mite numbers and more recently recapping. Especially as some of these are often expressed in tandem with the forage and climatic ebbs and flows of my locality. These behaviours are inherent to colonies with resistance to Varroa and the differences in those colonies which are less capable is quite apparent in both behaviours and mites. Indeed, it has been a great pleasure to have had Prof Stephen Martin tie uncapping/recapping, low mite fertility together, I had often been confused seeing multiple behaviours and never one dominant trait. My first colonies were from a free-living tree colony. Mother and daughter colonies lasted six and seven years respectively. The high level of natural selection facing free living colonies, incorporating those layers of selection and evolutionary dead ends into my beekeeping, being conscious of my colonies’ health and shepherding the situation in a positive direction, is where I would attribute our success.

Gareth Trehearn, (Manchester)

I originally got into beekeeping by attending a two-day course arranged by my local beekeeping association. I approached a local beekeeper and offered to help in return for some coaching. A few months after I started volunteering at his apiary, he suddenly fell ill, and I ended up running his hives for the rest of the season. I was hooked and the ‘Friends’ of a local park got in touch about a piece of waste ground that I could keep bees on and so I set about getting some bees. I was advised to buy a Nuc as my first colony. However, I’d done a bit of research online, and really wanted to have locally adapted bees. I purchased the equipment and decided, instead, to advertise for swarm collection online and a few weeks later I had 4 hives of bees. My initial reason for not chemically treating the bees or feeding them sugar syrup, was because I wanted to produce honey in its purest form for the family’s consumption. I recoiled at the thought of sublimating oxalic acid into my hives, for which I had to wear full PPE and breathing equipment, and how it would affect the bees and honey. I was aware that the usage instructions required there to be no supers on the hives during treatment, but I was also hyperaware that bees reorganise their colony throughout the year and could just as easily mix honey that had been in contact with oxalic acid with honey for harvesting. In those first few years, I didn’t observe any noticeable Varroa infestations. I continued as a hobbyist beekeeper until Covid hit in 2020 and so again advertised to collect swarms online. That spring and summer I was inundated with requests to collect swarms, presumably because so many more people were at home instead of at work and I finished the season on 49 hives. Because I hadn’t experienced the losses that people spoke about from Varroa, I didn’t have the fear about going treatment free on a larger scale. I’ve currently got 100 hives, all of which have come from swarms or from splitting my strongest hives and I don’t see any unexplained losses or sickness amongst the colonies. While varroa has not caused any significant impact on my bees' survival rates, I acknowledge that my methods may not work for everyone.

www.manchesterhoneycompany.com

Dr Fred J Ayres (Lune valley, Lancashire)

I took up beekeeping in 2000 and after taking several conventional courses, acquired my first nucleus the following year. In 2002 my colony swarmed, and I housed the swarm and acquired another nucleus. By 2005 I had 15 colonies on two sites. At this point I realised that I simply did not have the time to manage these colonies using conventional beekeeping techniques and decided that I either had to give up the hobby or find an alternative approach that was less intrusive and less time consuming.

One aspect that concerned me was the regular usage of chemicals to treat the bees. By this time varroa had been in the UK for some 15 years and, despite the ever-growing range of treatments on the market, nothing seemed to work. Two other factors concerned me. If the beekeeper had to wear a range of protective clothing whilst administering some of these treatments, could they really be harmless to the bees? The other was that despite the dire warning about honeybees dying out if beekeepers did not treat their bees, the number of untreated feral colonies in my area was steadily increasing. So, I stopped treating in 2006 and have not treated since. Since then, I have maintained 8 colonies in my home apiary with only 3 losses, none of which were due to varroa.

In 2016 I was instrumental in setting up Lune Valley Beekeepers (see video below), a new club focused on minimal intervention, treatment free beekeeping, in well insulated hives. The Club now has over 60 members, none of which treat their bees. We closely monitor our colony losses, and none have been due to varroa. We strongly advise our members not to bring bees into our area to avoid bringing in further varroa and have set up a breeding section at our Club apiary to be able to provide members with healthy bees, adapted to our local environment. We also train our members to carry out a regular programme of comb exchange at their spring inspections to ensure that there is no build-up of varroa within the hive. Whilst these measures may not eliminate varroa, our experience is that colonies seem to be able to manage the pest without treatment, provided it is not being constantly reintroduced by importing bees into the area.

www.lunevalleybeekeepers.co.uk

Patrick Laslett (Norfolk)

I now keep my 40-50 colonies in Norfolk entirely treatment-free. One of my apiaries has not been treated for nearly ten years now and the rest of my colonies have not been treated for the last five years. I started beekeeping in the early nineties and my journey to treatment free beekeeping was a slow one.

First, like many other beekeepers, I used the whole gambit of chemical mite control methods from strips to trickle on and finally to pads. In the end I was getting concerned that the cure was worse than disease and wanted a chemical free solution to the problem. As Varroa increased and bred in capped cells I decided to treat it as a brood problem, and I began removing the brood from some of my colonies in a modified version of the shock swarm process. My site www.miteout.co.uk documents what I was doing for a few years.

After a few years I felt brave enough to stop treating my colonies in one apiary and that apiary became my treatment-free apiary. After a few more years I stopped treating all my bees whatever apiary they were in. I think I did lose more colonies as a result but gradually over time the colonies that I lost were replaced by the offspring from surviving colonies or the empty brood boxes were re-filled by a swarm looking for a new home. For a few years now I have noticed 'bald brood' in some of my colonies without knowing exactly what is going on. I have always collected and kept swarms. Nowadays most swarms are almost certainly coming from my beekeeping neighbour's colonies. But some I think are from the now small stock of feral colonies that still exist out there in the wild. So, I think all swarms are well worth collecting, keeping and assessing. I still use my Varroa shook method when selling a colony and I still document my visits to my original treatment free apiary. https://www.youtube.com/@honeybeesforsale

Now I will be taking much more notice of bald brood and start selecting the best from those colonies where I find bald brood.

Monica Barlow the Broadstone Bees (South Wales)

This is a case study in observation of bee colonies in a natural apiary over 13 years from 2011-2023. Colonies are free-living although their nest cavities are man-made. We monitored their activity, survival and swarming. The aim of the study was to determine whether a resilient population of honey bees could survive and thrive in an ordinary landscape in South Wales: the apiary site is not protected, isolated or particularly noted for bee forage.

Honey bee colonies are surviving and thriving without intervention in this location, in numbers sufficient to let them reproduce successfully, spread and maintain their population. Since observations began in 2011, 23 colonies have survived through their second winter or beyond. The project has confirmed that honey bees are surviving varroa in South Wales without the need to treat or feed them. For much more details and the entire story Click here

NORWAY

Dr. Melissa Oddie – The Norwegian beekeepers Association

Melissa is the first person to link recapping to Varroa resistance and so is a key person in the Varroa resistance story. Since it was this trait that led to the mechanism of resistance to be explained for the first time. Melissa's personal journey of discovery and understand of Varroa resistant makes for a fascinating read. Click here to access the full story.

Further Information

BBKA special issue

This leaflet provides the information written for beekeepers on the background to how colonies become resistant using the scientific literature. It discuss the roles of DWV and Varroa reproduction and hygienic behavioural that has allowed the bees to become resistance. It then gives some advice on how to measure recapping and mite removal. Its essential background reading.

The leaflet is available from the BBKA shop for £4.00.

The button below takes you to the BBKA website.

A review of the booklet can be found here.

General articles published in the UK bee magazine

Varroa-Resistance: A team update BBKA News October 2021. This provides an update from the Salford team studying mite resistance.

Naturally Varroa- resistant bees in the UK. Bee Craft Jan 2021. This article explains the mite resistance mechanism. The term NVR which means 'natural Varroa resistant' but that is no longer used as there are too many anagrams.

Natural Varroa resistance: the end of chemical control? . Bee Craft July 2022. This article discusses how resistance develops and increases colony survival. It came with a free poster and copy is in this article.

David Heaf's personal website and books on treatment free beekeeping. A real wealth of information.

Good news for Treatment-Free Beekeeping. BBKA News July 2022. Clive and Shan Hudson article about varroa resistance along with information from Chris & Joe Ibberston and other treatment free beekeeping.

Is Varroa Treatment-free Beekeeping an Option for ALL Beekeepers. BBKA News July 2022. Stephen Martin discusses the evidence behind now is the time to go treatment-free.

European Honeybees in Cuba are Calm, Productive and Varroa-Resistant. BBKA News April 2023. Stephen Martin reveals the hidden world of beekeeping in Cuba where the bees are fully resistant against the Varroa mite.

Behandlungsfreie Imkerei in Gwynedd, Wales / Treatment free beekeeping in Gwynedd, Wales https://vimeo.com/157019200 Takes you to a 5min vimeo video about David Heaf made in 2015 and treatment free beekeeping

Videos

Dr. David Heaf story

This video follows David's logic and why he stopped all Varroa treatment. This book 'Treatment free beekeeping' contains a wealth of knowledge and many other examples of treatment free beekeepers

Has Varroa Lost its Sting

This the story of how the Hudson's in North Wales became Varroa resistant beekeepers

Measuring resistant traits

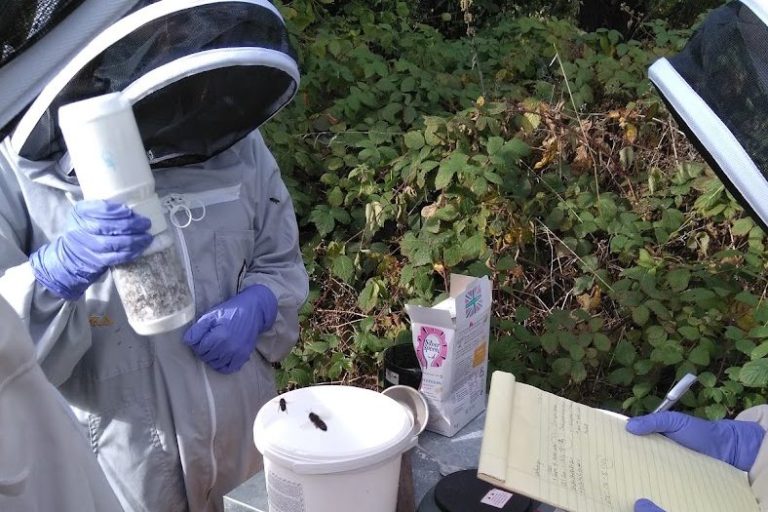

This demonstrates what equipment you need and how to use it to measure recapping of brood cells and mite removal rates but inserting living mites into cells.

Lune Valley Beekeepers

Fred Ayres explains the reasons behind the formation of this group of like minded beekeepers that manage their colonies without Varroa treatment.

Prof. Stephen Martin

Population Biology of Varroa

Part I. Stephen's talk at the Danish Beekeeping Conference 2023, talking about how Varroa in association with Deformed wing virus can kill a honeybee

Prof. Stephen Martin

Varroa resistance mechanism

Part II. Stephen's talk at the Danish Beekeeping Conference 2023, talking about the mechanism of Varroa resistance, and how the honeybees evolve to deal with Varroa

BBKA 2023 Conference talk

Varroa resistance: personal and practical views of five treatment-free beekeepers

Recording of the BBKA Haper Adams Beekeeping Conference 2023, where 5 beekeepers talk about their personal dealings with keeping Varroa resistant colonies and give practical advice.

NHS 2024 Conference talk

Steve Riley: "The Honey Bee Solution to Varroa

Author of the excellent beekeeper focuses book: The honey bee solution to Varroa. Steve explains what is Varroa resistance, and how beekeepers can select for Varroa resistant honeybees.